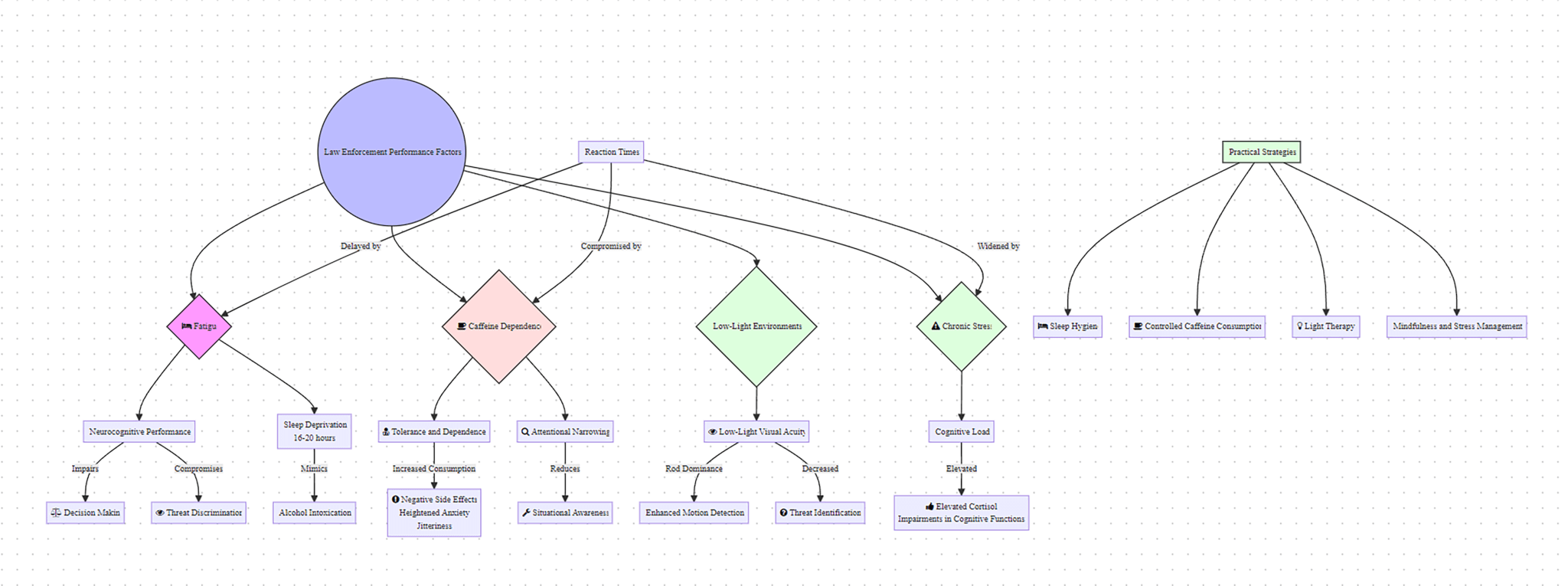

For the average law enforcement officer, the capacity to rapidly discern, assess, and respond to evolving threats is not just a skill—it’s a lifeline. In critical situations, delays in reaction time or misinterpretations of a threat can have fatal, and severe legal, consequences. Unfortunately, the demands of the profession, including extended shifts, chronic sleep deprivation, reliance on caffeine, and often consistently operating in low-light environments, all degrade, and slow down, the very cognitive and sensory processes that officers rely on most. Understanding the ways in which these factors compromise performance is critical for officers, the agencies that have policies that govern these arenas, and responsible armed citizens alike.

Fatigue and Its Influence on Cognitive Performance

Fatigue is more than just a feeling of tiredness. At a neurobiological level, prolonged wakefulness leads to significant impairments in the brain’s executive functioning, particularly within the prefrontal cortex, which governs decision-making, impulse control, and threat discrimination. This is vital, not just for police officers but real world violent interactions, where split-second decisions often determine the outcome of critical incidents. Sleep deprivation, even for a period as short as 16-20 hours, may mirror cognitive impairments associated with alcohol intoxication. In this state, an officer’s ability to evaluate a situation, weigh risks, and make sound decisions may become severely compromised.

Equally concerning is the deterioration of sensory processing under conditions of fatigue. Research shows that reaction times to external stimuli slow significantly, and officers may struggle to interpret visual or auditory cues accurately, particularly in high-stress environments. The decline in sustained attention, or vigilance, poses a unique danger, as it can delay the recognition of a threat and the initiation of an appropriate response, leaving both officers and citizens vulnerable. This can be understood easily by those who experience hyper-vigilance, and then the after effects of such a state that may dip below the thresholds of their normal state, that is to say – to fall into a state of hypo-vigilance.

Consequences of Caffeine Overuse

Caffeine is a ever present tool used by officers to combat fatigue, but its overuse introduces its own set of problems. While caffeine blocks adenosine, a chemical that promotes sleep, chronic overconsumption leads to tolerance and dependence, forcing officers to consume higher amounts to achieve the same effect. This cycle not only diminishes caffeine’s efficacy but also introduces negative side effects, such as heightened anxiety, jitteriness, and impaired motor coordination. These issues can undermine the very precision required in high stress, critical scenarios, especially when handling a firearm, tactical operations, and other fine motor processes that are required on demand.

Excessive caffeine use can create a cognitive condition known as attentional narrowing, where the user becomes hyper-focused on a single task or threat to the detriment of their situational awareness, especially during a high risk, critical, “adrenaline dump” type situation. In these moments, peripheral threats or changing environmental cues may go unnoticed, increasing the likelihood of failure to notice other threats, or dangerous circumstances. In fact, overreliance on stimulants without proper training in stress management (Force on force), and applicable skillset development, can amplify risk, especially when an officer is already fatigued and overstressed. In a previous article “The Adrenaline Wave” I covered what the effects of being under high stress in a critical situation does to the average officer and citizen.

Visual Acuity in Low-Light Encounters

Low-light conditions present additional challenges to law enforcement officers, particularly when they are required to make life-or-death decisions based on visual information. The human eye is optimized for daylight conditions, relying on cone photoreceptors to provide clarity and detail. However, in low-light conditions, rod photoreceptors become the dominant players, and while they enhance peripheral vision and motion detection, they offer far less visual acuity. This transition between well-lit and dimly lit conditions results in a phenomenon known as dark adaptation, which can temporarily impair vision as the eye adjusts. During this period, officers may struggle to discriminate active threats, putting them in danger.

Low light slows the processing of visual stimuli. The transduction of light signals into neural impulses becomes less efficient, leading to delayed recognition and interpretation of what is seen. This slows down overall reaction time, as the brain requires more stimulus to orient and act quickly. While responding to fast-paced, high stress, and critical situations that officers regularly find themselves operating in, these delays can be fatal. The ability to rapidly assess a situation, determine the level of threat, and respond appropriately is compromised, increasing the likelihood of mistakes under real world pressure. The compounding stressors of high heart rate, dopamine / adrenaline / cortisol flood, exponentially aggregate the potentional for untrained, or poorly trained, skillset failures. This is where we see officer’s drop magazines, hold onto cell phones, run away from cover, freeze, and make other stress-induced mistakes under low-light.

Cognitive Load and Stress

Stress is an inherent part of the job, and the reality of interpersonal conflict, but chronic exposure to high stress situations without adequate recovery takes a heavy toll on cognitive performance. When the brain is exposed to prolonged stress found in the form of double or prolonged work shifts, interpersonal drama, as well as physical pain due to training, and lack of proper diet, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis becomes dysregulated, leading to elevated cortisol levels. While cortisol helps in acute stress situations by preparing the body for fight-flight-freeze responses, sustained high levels of cortisol impair cognitive flexibility and working memory. These functions are crucial for integrating sensory inputs and making rapid decisions, particularly in dynamic environments where the situation is constantly evolving. Though cortisol levels effects are anecdotal at best, especially in a one off scenario, the prolonged and continuous lack of self regulation, in the form of sleep and relaxation, may compound other effects in the context of cognitive load.

As stress intensifies, the brain narrows its attentional focus, making it more difficult for officers to process and integrate information from multiple sensory inputs. This effect is amplified by the combination of fatigue and caffeine overuse, which further depletes cognitive resources, especially over time. Under these conditions, officers may struggle to maintain situational awareness, leading to errors in threat discrimination and decision-making. Compound this by Hick’s Law, as previously mentioned in “Understanding Vision, Cognition, and Response: The Complexities of Reaction Time in the Real World” and you have a potentially deadly cocktail of circumstances.

Other considerations that may directly effect the ability to process and respond to a threat are diagnosed issues like Shift Sleep Disorder and Shift Work Sleep Disorder, which nearly every first responder is primed to suffer from.

Reaction Times, Reactionary Gaps, and Physical Response Deficits

Reaction time is critical in law enforcement, and interpersonal violence, where the ability to quickly identify and act on a threat can mean the difference between life and death. Reactionary gaps—the time between recognizing a threat and initiating a response—are widened significantly by fatigue, stress, and environmental factors such as low light. Neurologically, reaction time is a function of how efficiently the brain can process sensory information and send signals to the motor system. Fatigue, caffeine overuse, and stress impair, and clog, these neural pathways, slowing the transmission of signals and delaying physical responses.

An officer’s reaction time, within their reactionary gap, is directly disposed to the level of attention given to an external stimulus. Reactionary gap is the measure of that attention in the context of a high stress situation.

Studies show that reaction times can be delayed by as much as 20-30% when an individual is sleep-deprived. This is further exacerbated when coupled with caffeine dependence. In situations where split-second decision-making is essential—such as drawing a weapon, “moving off the x,” and engaging a suspect—these delays can be fatal. Officers may find themselves slower to react to threats, or worse, reacting inappropriately due to impaired cognitive processing. Officers may find themselves unable to take the action they may have previously believed they could, or should have, due to lack of proper skillset development. This is covered in a previous article “Why Repetition Is the Path to Mastery and the “Rise to the Occasion” Myth” – the first step to mitigation is the mastery of applicable skillsets through proper repetition.

Implications and Strategies for Overcoming Deficits

Despite the profound physiological and cognitive impacts of fatigue, stress, and stimulant overuse, several strategies may help overcome these effects and enhance performance in law enforcement, and in the arena of interpersonal violence.

Get Sleep: Establishing proper sleep hygiene is critical for maintaining optimal cognitive performance. An officer should prioritize sleep between shifts. Research suggests that 7-9 hours of sleep per night is necessary to fully restore cognitive capacities. Individual officers should also educate themselves on the importance of sleep hygiene, including strategies for improving sleep quality, such as limiting exposure to blue light before bedtime, creating a restful sleep environment, and all the requirements of optimal sleep, and the recovery experience after/before shifts.

Control The Caffeine: Officers should be educated on the pharmacokinetics of caffeine, including its half-life and the risks of tolerance and dependence. Instead of trying to compete with one another for how much caffeine they can intake every shift, the use of caffeine should be tactical, strategic in nature to maintain alertness without over-stimulation, when necessary. Combining caffeine with l-theanine, an amino acid that promotes relaxation without sedation, has been shown to improve focus while reducing anxiety—a particularly useful tool for officers in high-stress situations. However, in a recently published study “Beyond the Buzz: Do Energy Drinks Offer More Than Caffeine for Mental and Physical Tasks?” found that there were no significant differences between the effects of the cafeine and the energy drinks on any measure, physical or mental.

Our findings suggest that, for the measures assessed in this study (i.e., sustained attention, mood, handgrip strength, and push-ups), the additional ingredients in the energy drink did not provide any substantial benefits beyond the effects of caffeine in our sample of active men and women. We posit that the primary differences in outcomes between our study and others showing positive effects of energy drinks are due to the specific blend of ingredients beyond caffeine and the caffeine content.

Beyond the Buzz: Do Energy Drinks Offer More Than Caffeine for Mental and Physical Tasks?

The question has to be asked, therefore, will simply taking a good quality caffeine pill (200mg, or 400mg) sourced from a verifiable lab, while mitigating the intake of sugars, vitamins, and other chemicals commonly found in energy drinks, before a known hazard of police activity a better protocol? This is a topic that should be considered and may be developed further in future.

Force on Force: Consistent, and purposefully driven skillset development for the goal of pattern recognition by using real world examples of deadly force situations, especially in low light, contrasted with the direct instruction of overcoming sensory barriers of overstimulation, has proven itself vital in allowing officers to succeed. Applying these skillsets in high stress low light situations effectively, directly impact an officers ability to overcome real world deadly force encounters.

Seek Medical Guidance and Utilize Preventative Resources: Many law enforcement agencies offer excellent healthcare options, including access to a wide range of preventative services. Officers should prioritize regular health assessments, including blood tests, maintaining a balanced diet, and seeking professional medical advice for conditions specific to first responders, such as shift work sleep disorder. While some issues, like the challenges posed by irregular shift work, may not have a complete solution, there are mitigation strategies—such as targeted lifestyle adjustments and, in some cases, medication—that can help officers optimize their performance during their shifts. Taking advantage of these resources ensures that officers are functioning at their best, both physically and mentally.

Train Like You Fight: High-intensity interval training (HIIT) has also been shown to improve stress resilience by balancing the body’s response to stress and enhancing overall physical conditioning. While this can have detrimental effects if done daily, the need for intentionally pushing cardiac, and muscle, functions to a high level have a direct application to interpersonal violence in the real world. This can be done through applicable skillset development sports like BJJ, but should be regimented to aid in the skillset developments that the individual officer may require in the application of violence in the real world. The goal is to know how you function, mentally and physically, in high intensity situations and allow yourself to intentionally take action, not be overcome by the Adrenaline Wave.

The intersection of fatigue, caffeine dependence, low-light environments, and chronic stress places significant neurophysiological burdens on law enforcement officers, impeding their ability to rapidly and accurately respond to evolving threats. By understanding the mechanisms through which these factors affect visual perception, cognitive processing, and reaction times, police officers can adopt proactive measures to mitigate these deficits. Implementing strategies aimed at improving sleep hygiene, controlling caffeine consumption, enhancing visual acuity, and managing stress will significantly improve officers’ performance in the field, ultimately leading to safer outcomes for both officers and the communities they serve.

Developing a deeper understanding of the brain-body connection in high-stress situations, police officers can be equipped with the tools necessary to not only perform optimally under pressure but also to maintain long-term psychological and physical well-being.

Sources:

- Killgore, W. D. S. (2010). Effects of sleep deprivation on cognition. Progress in Brain Research, 185, 105–129.

- Bonnet, M. H., & Arand, D. L. (2003). Clinical effects of sleep fragmentation versus sleep deprivation. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 7(4), 297-310.

- Smith, A. (2002). Effects of caffeine on human behavior. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 40(9), 1243-1255.

- Sternberg, S. (1969). Memory-scanning: Mental processes revealed by reaction-time experiments. American Scientist, 57, 421-457.

- Riemann, D., Spiegelhalder, K., Feige, B., et al. (2010). The hyperarousal model of insomnia: A review of the concept and its evidence. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 14(1), 19-31.

- PEREIRA, (2024) Beyond the Buzz: Do Energy Drinks Offer More Than Caffeine for Mental and Physical Tasks? Int J Exerc Sci. 2024; 17(1): 1208–1218.

Leave a comment