Why Repetition Is the Path to Mastery and the “Rise to the Occasion” Myth: The Neuroscientific and Psychological Foundations of Skill Acquisition

The acquisition of any skill, whether cognitive, motor, or a combination of both, is a complex process deeply rooted in the principles of neuroplasticity, synaptic plasticity, and the development of procedural memory. Despite the popular notion that individuals can “rise to the occasion” and perform exceptionally under stress without prior practice, scientific evidence strongly suggests otherwise. We explore the mechanisms that underpin skill learning, emphasizing the essential role of repetition and debunking the myth that spontaneous competence can emerge in the absence of practice.

Neuroplasticity and Synaptic Plasticity: The Biological Underpinnings of Skill Learning

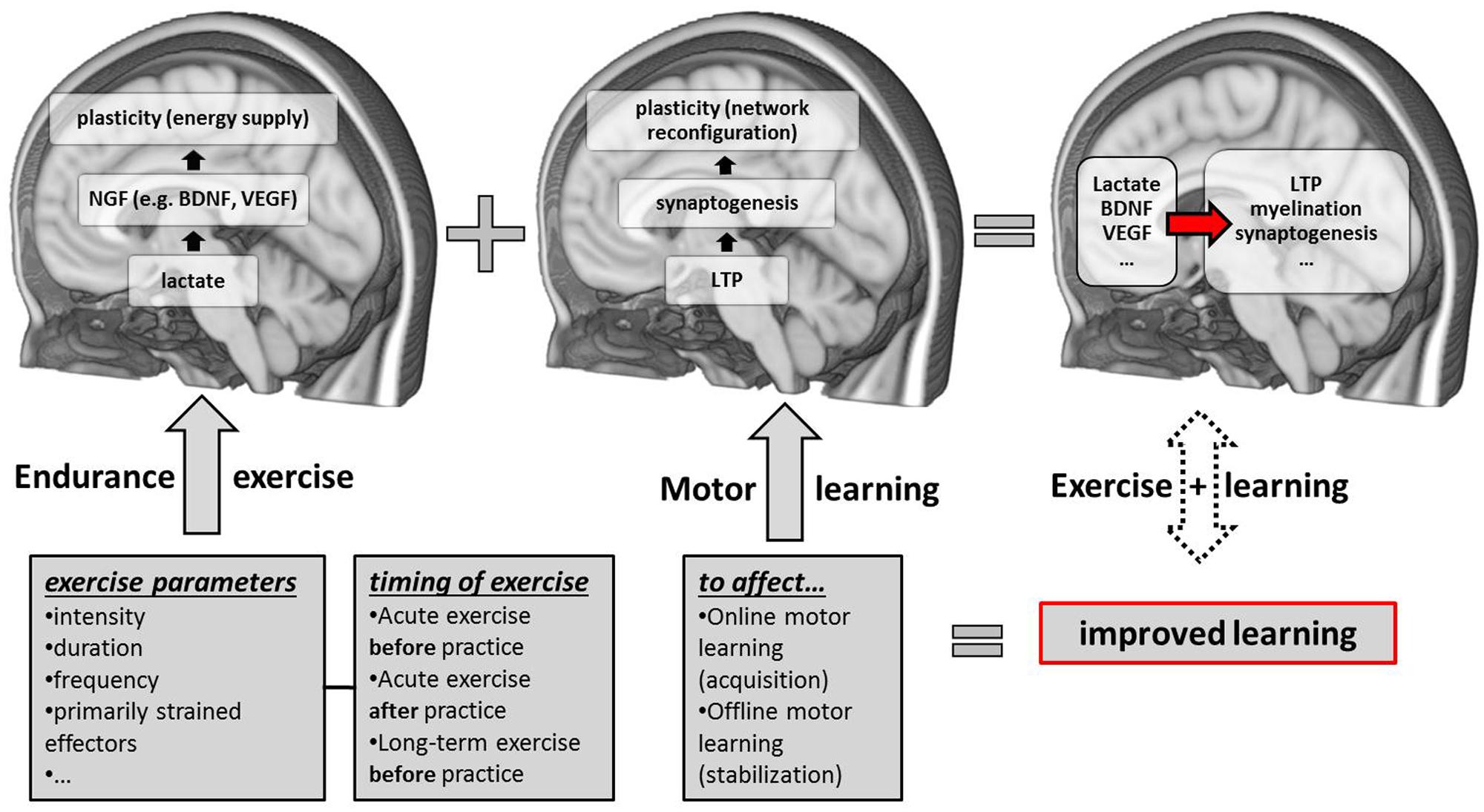

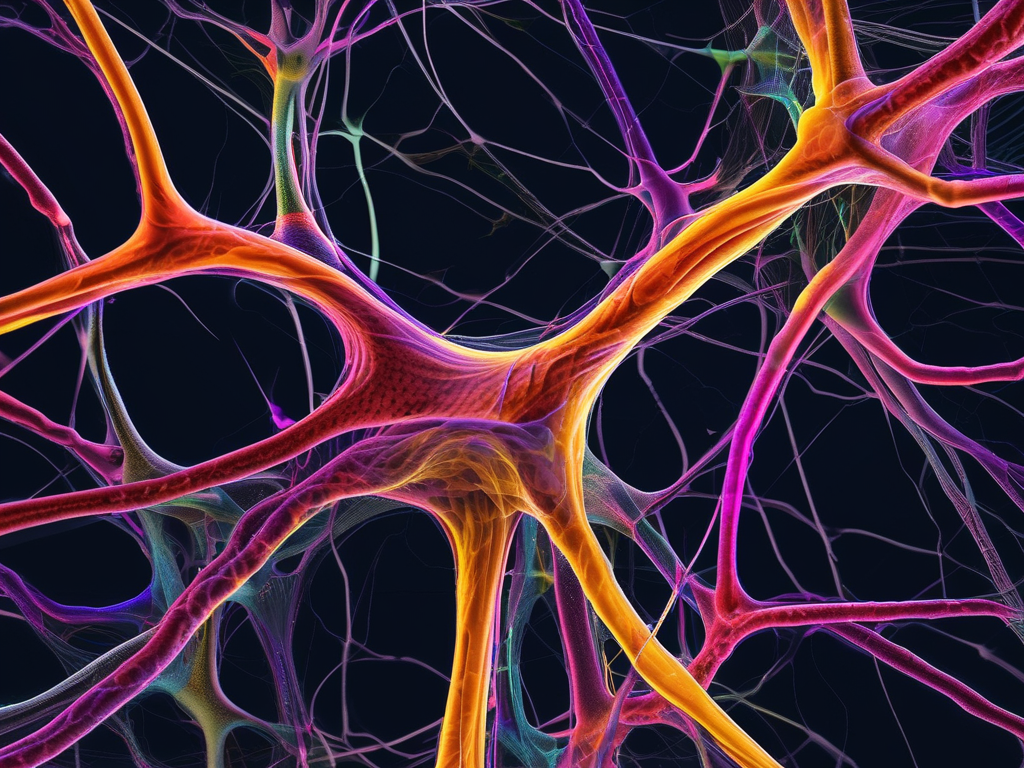

At the core of skill acquisition lies neuroplasticity, the brain’s remarkable ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections in response to learning and experience. This process is particularly important when it comes to learning new skills. Each time a skill is practiced, specific neural circuits are activated and reinforced. The more these circuits are used, the stronger they become, a concept known as synaptic plasticity. This strengthening of synaptic connections is fundamental to the process of learning, as it enables the brain to encode and retain new information and abilities.

The process of synaptic plasticity involves long-term potentiation (LTP), where repeated stimulation of a synapse increases its strength. LTP is considered one of the primary mechanisms underlying learning and memory. When a person practices a skill repeatedly, the synapses involved in that skill undergo LTP, becoming more efficient at transmitting signals. This increased efficiency is what allows the skill to be performed with greater speed, accuracy, and automaticity over time.

Hebbian learning, encapsulated in the phrase “cells that fire together, wire together,” further explains how repeated practice leads to the formation of strong neural networks . When neurons are repeatedly activated in a coordinated manner, the synaptic connections between them are strengthened. This process not only makes the skill easier to perform but also integrates it more deeply into the brain’s neural architecture. In the absence of repetition, these synaptic connections remain weak, and the skill cannot be performed reliably, particularly under conditions of stress.

Neurons that fire together, wire together.

Hebbs

The more you do something, the more your brain responds to support that activity. The less you do something, the brain “prunes” the connections in order to strengthen those that you do use.

The Role of Repetition in Cognitive and Motor Skill Acquisition

The transition from conscious effort to unconscious competence in skill learning is a progressive and structured process, heavily reliant on the principle of repetition. Initially, when a new skill is introduced, the brain engages in high levels of cognitive processing. This stage is characterized by significant involvement of the prefrontal cortex, responsible for executive functions such as decision-making, planning, and problem-solving. The cognitive load at this stage is substantial, as the brain is actively trying to decode and understand the new task.

As repetition continues, the brain begins to streamline the process, shifting the skill from the realm of conscious, deliberate effort to that of automatic, unconscious execution. This shift is facilitated by the gradual involvement of the basal ganglia, a group of nuclei in the brain associated with habit formation and procedural memory. Procedural memory is a form of long-term memory that stores information about how to perform tasks. Through repeated practice, the skill becomes embedded in procedural memory, allowing it to be executed with minimal conscious thought.

In the domain of motor skills, such as those required for athletic performance or playing a musical instrument, repetition is critical for the development of muscle memory. Muscle memory refers to the process by which the body memorizes motor tasks through repetition, allowing for more precise and automatic execution of those tasks. The cerebellum, a brain region involved in coordinating movement and fine motor control, plays a key role in this process. Through repeated practice, the cerebellum fine-tunes the motor commands, enabling the body to perform complex movements with greater efficiency and accuracy .

The process of automatization, where a skill becomes automatic through repetition, is crucial for high-level performance. Without sufficient repetition, the brain must continue to engage in conscious control over the skill, which is not only inefficient but also prone to error, especially under stress. The transition to unconscious competence, where the skill can be performed effortlessly, is the ultimate goal of repetition and is achieved only through sustained, deliberate practice.

Skill mastery is a progressive journey that begins with conscious incompetence, where individuals recognize their lack of skill and the challenges involved in learning. As they engage in deliberate practice, they move to conscious competence, where the skill is acquired but requires focused attention and effort to execute. With continued practice and experience, the skill becomes second nature, leading to unconscious competence, where it is performed effortlessly and automatically. This transition from conscious incompetence to unconscious competence is underpinned by cognitive development, metacognition, and the automatization of cognitive processes. This can only be achieved through focused repetitions on the given skillsets and experience within the applicable skillset field.

Stress, Cognitive Load, and the Fallacy of “Rising to the Occasion”

The popular belief that individuals can “rise to the occasion” and perform exceptionally well under stress without prior practice is largely a myth when scrutinized through the lens of cognitive science and neurobiology. Stress, particularly acute stress from elevated cardiac levels due to dopamine and adrenaline, has a profound impact on cognitive function, often impairing the very abilities needed for complex skill execution.

Under stress, the body’s fight-or-flight response is activated, leading to a cascade of physiological changes, including increased heart rate, elevated levels of stress hormones (such as cortisol, dopamine, and adrenaline), and heightened arousal. While these changes are designed to prepare the body for immediate physical action, they can be detrimental to cognitive functions such as working memory, attention, fine motor control and decision-making. The prefrontal cortex, which is critical for these higher-order cognitive processes, is particularly vulnerable to the effects of stress.

The Yerkes-Dodson law, a well-established psychological principle, posits that there is an optimal level of arousal for peak performance. This law suggests that moderate levels of arousal can enhance performance by increasing alertness and focus. However, when arousal levels become too high, as they often do under acute stress, performance begins to deteriorate. This decline is particularly pronounced in tasks that require fine motor control, complex decision-making, or the execution of unpracticed skills.

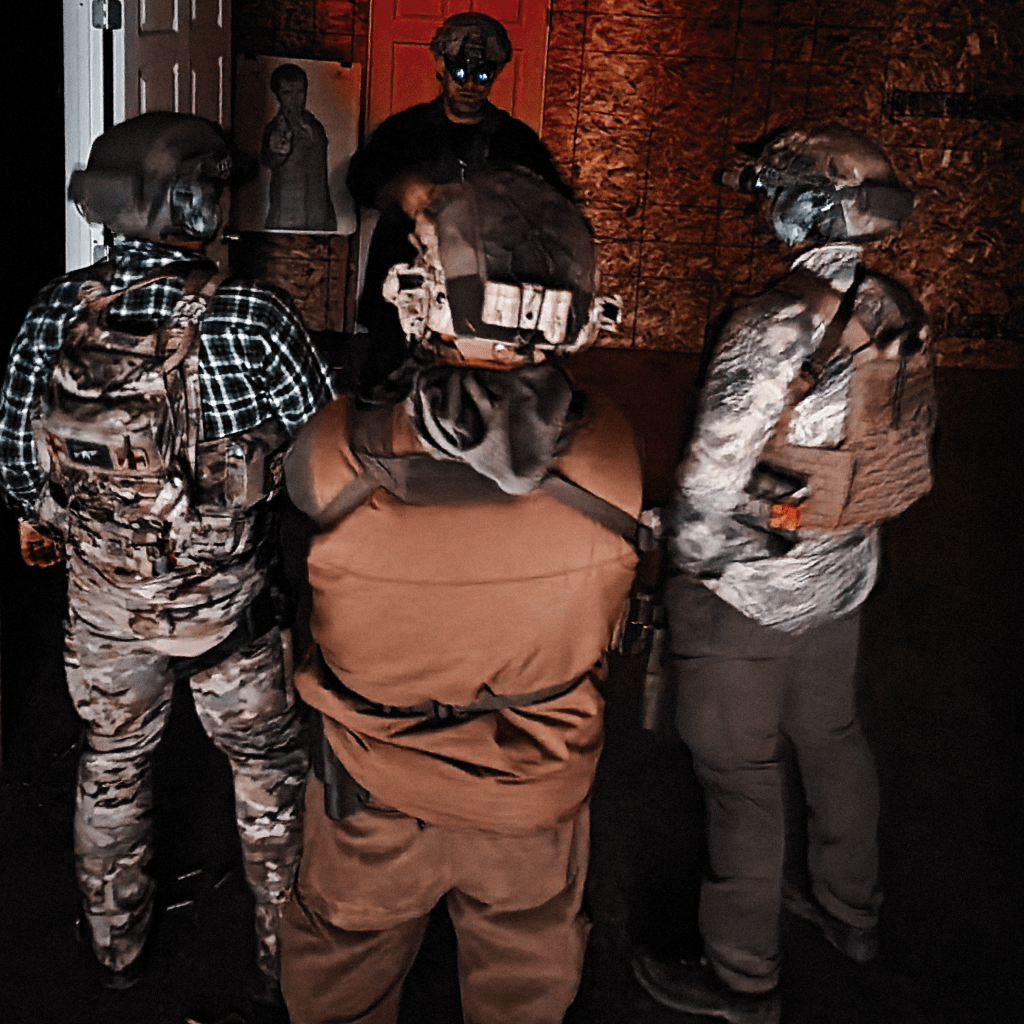

For skills that have not been practiced sufficiently, the level of stress required to “rise to the occasion” typically exceeds this optimal arousal level, leading to cognitive overload and performance failure. The brain, in such situations, defaults to the most well-established neural pathways—those that have been reinforced through repetition. If the skill has not been practiced enough to create these robust pathways, the individual is unlikely to perform effectively. This is why the idea that one can spontaneously execute complex skills under stress without prior repetition is not only unrealistic but also contradicts the principles of neuroscience and psychology. This applies to every skillset a person actively, or passively, learns throughout their lives.

The physiological effects of stress further compound the difficulty of performing unpracticed skills. Stress-induced changes, such as increased muscle tension, reduced fine motor control, and narrowed attentional focus, can severely impair performance. These effects are particularly detrimental when the individual lacks the muscle memory or procedural memory required to execute the skill automatically. In such cases, the body’s instinctual responses, (also known as natural responses) which are not fine-tuned for the specific task, take over, leading to suboptimal or even catastrophic outcomes.

The Imperative of Repetition for Mastery

Given the intricate processes involved in skill acquisition, it becomes evident that repetition is not just beneficial but essential for the mastery of any skillset. The repeated practice of a skill allows for the gradual refinement of neural pathways, the consolidation of procedural memory, and the development of muscle memory. These processes are what ultimately enable anyone practiced enough to perform a skill with precision, accuracy, and minimal conscious effort.

Deliberate practice, characterized by focused, goal-oriented repetition, is particularly important in this context. It is through deliberate practice that skills are honed, errors are corrected, and performance is optimized. Research in skill acquisition consistently demonstrates that the quantity and quality of practice are the primary determinants of mastery. Without sufficient repetition, the brain and body lack the necessary experience to perform the skill reliably, especially under conditions of stress.

For educators, coaches, instructors, and individuals seeking to develop expertise, the emphasis should be on fostering consistent, deliberate practice. By doing so, the brain is given the opportunity to form the strong neural networks needed for automaticity, ensuring that the skill can be executed flawlessly even in high-pressure situations. In contrast, reliance on the idea of “rising to the occasion” without the foundation of repeated practice is a misguided approach that undermines the potential for genuine mastery.

The concept of “rising to the occasion” also ignores the role of experience in stress inoculation. Individuals who have practiced a skill extensively are not only better at performing the skill itself but also more resilient to the effects of stress. This resilience is a result of both the physiological adaptations that occur with repeated exposure to stress and the psychological confidence that comes from knowing the skill is well-practiced. In essence, those who have put in the repetitions are better equipped to handle the cognitive and emotional demands of performing under pressure.

The mastery of any skill is a product of repeated practice, grounded in the principles of neuroplasticity, synaptic plasticity, fundamentally applicable experience, and procedural memory consolidation. The myth of “rising to the occasion” without prior practice is not supported by scientific evidence and overlooks the critical role of repetition in embedding skills into the brain’s neural architecture. For those seeking to achieve excellence, the path is clear: invest in deliberate, consistent practice, and the brain will respond by making the skill an effortless, automatic part of your repertoire. Disregarding this truth in favor of the fallacy of spontaneous competence is not only misguided but also undermines the potential for true mastery, particularly in high-stress situations where only the most well-practiced skills can be reliably executed. This scientific explanation of repetitions, and the types of naturally ingrained responses we have as humans, does not speak to the cognitive processing required to apply a given skillset under real world stress that have multi-tiered orders of effects, such as legal, ethical, and moral reprocussions.

Sources

- Hebb, D. O. (1949). The Organization of Behavior: A Neuropsychological Theory. Wiley.

- Bliss, T. V. P., & Collingridge, G. L. (1993). A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature, 361(6407), 31-39.

- Doyon, J., & Benali, H. (2005). Reorganization and plasticity in the adult brain during learning of motor skills. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 15(2), 161-167.

- Yerkes, R. M., & Dodson, J. D. (1908). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology, 18, 459-482.

- Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363-406.

- McEwen, B. S. (2007). Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiological Reviews, 87(3), 873-904.

- Gazzaniga, M. S., Ivry, R. B., & Mangun, G. R. (2018). Cognitive Neuroscience: The Biology of the Mind (5th ed.). W.W. Norton & Company.

Leave a reply to Improving Police Response: Combatting Fatigue and Stress – Secønd Støic Cancel reply