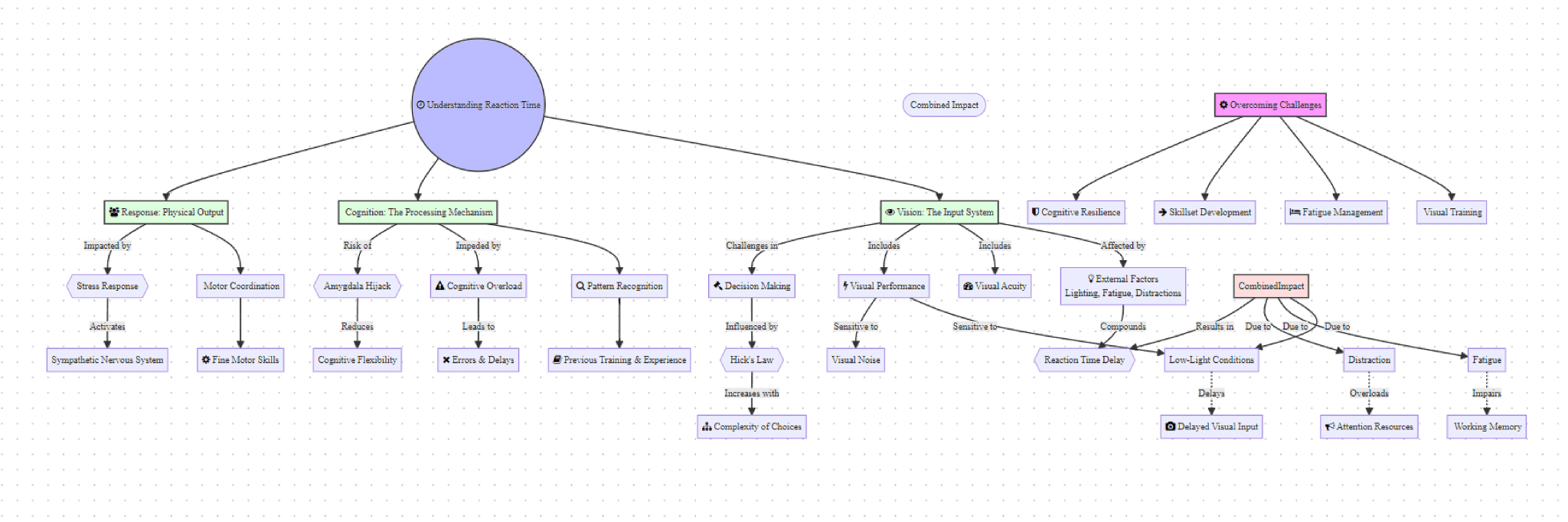

In high-stakes professions like law enforcement, the ability to respond quickly and effectively can be the difference between life and death. However, reaction time—often reduced to a singular metric of speed—reflects a multilayered interaction between vision (the input system), cognition (the processing mechanism), and physical response (the output). These three systems are dynamically impacted by various external factors such as lighting conditions, fatigue, and distractions.

For police officers specifically, but also to the average responsible armed citizen, especially those who are not elite athletes or specifically conditioned to operate under stress, these influences compound in ways that can slow their reaction from milliseconds to seconds.

In the reality of police work, reaction time is the delay between perceiving a threat and physically responding to it, and this delay is heavily influenced by conditions on the ground. Under stress, an officer might encounter dim lighting during a night patrol, where identifying a suspect or weapon takes longer because the eyes struggle to adjust to low visibility. Fatigue from long shifts compounds this, slowing the officer’s cognitive processing—making it harder to recognize patterns or distinguish between a real threat and a benign situation. When distractions like noise, movement, or multiple suspects are added, the brain becomes overloaded, increasing the chance of missing critical details. Physically, even when an officer decides to act, the fight-or-flight response triggered by stress can reduce fine motor skills, causing delays in drawing a weapon or performing defensive maneuvers. These factors transform what should be split-second reactions into several agonizing seconds, which in police work, can mean the difference between life and death.

Vision: The Critical First Step

When we talk about “vision” in the context of reaction time, it’s essential to distinguish between visual acuity (the sharpness of sight) and visual performance (the speed and accuracy of visual processing). The latter, visual performance, is highly sensitive to external factors such as lighting conditions and the presence of visual noise.

In policing, just like for the average person in a high stress situation, officers are often required to make split-second decisions in low-light environments. This is particularly challenging because low-light conditions affect the retina’s ability to process light, especially in the photopic (well-lit) and scotopic (low-light) states. The retina’s rods, responsible for vision in dim lighting, have a much slower recovery time compared to cones, which function in bright light. The result? A delayed visual input under poor lighting conditions.

Further complicating this is the application of white light, which, while ideal for illumination, can also induce glare, a significant reduction in visual contrast, and ultimately, a slower time to visual recognition. This is often referred to as disability glare, which leads to an overexposure of the retina and delays the neural signal that is sent to the brain. For a police officer, this could mean the difference between identifying a weapon and mistaking it for a benign object.

Moreover, the complexity of visual input under stress is exacerbated by the brain’s need to filter relevant versus irrelevant stimuli. The neurobiological phenomenon known as attentional blink—a brief period during which the brain is temporarily “blind” to new stimuli after processing a prior one—can severely limit the capacity for rapid successive judgments. This blink is particularly prolonged under high-stress environments, which police officers frequently experience. This is not exclusive to dim, or low, light situations, as an oversaturation in stimuli, such as a crowd of people, can effectively slow down a police officer’s overall speed of reaction and decision making. Hick’s Law explains that as the number of possible responses increases, decision-making slows down, which is critical in policing where officers face a barrage of visual stimuli and must quickly assess various courses of action. Under immense visual pressure—such as multiple moving suspects or conflicting environmental cues—this cognitive load can stretch reaction time, forcing officers to navigate through more options, each adding delay to their response.

The time it takes to make a decision increases with the number and complexity of choices

Hick’s Law

Cognition: Pattern Recognition Under Pressure

The second phase of reaction time involves cognitive processing—essentially, the brain’s capacity to recognize and interpret visual input in context. Pattern recognition plays a crucial role here. Pattern recognition is not just about recognizing objects; it involves identifying relationships between elements within a visual scene, like the threat level of a suspect’s posture or movement.

Cognitive processing relies heavily on previous training and experience. However, for officers who lack advanced experience or specialized training, this phase can slow significantly. The brain relies on heuristics, mental shortcuts derived from previous experiences, to expedite decision-making. Yet, when facing unfamiliar or ambiguous situations, the reliance on these heuristics can lead to errors, delayed response, or cognitive overload. This also means that a person in this type of situation will never “Rise to the Occasion” and consistently fall to their lowest level of training in any given skillset.

Under stress, the prefrontal cortex (PFC)—responsible for higher-order decision-making and executive control—often cedes control to the more primitive amygdala, which governs emotional responses like fear and aggression. This phenomenon, termed amygdala hijack, results in a reduction of cognitive flexibility and a reliance on more automated, (should be interpreted as previous repetitions of skillsets appliable to the situation at hand) reflexive behaviors. For a police officer, this could translate into reduced situational awareness, an inability to reassess a rapidly evolving situation effectively, or to take decisive action due to untrained skillset crushing stress levels.

Fatigue plays a critical role in slowing reaction times for police officers, as it directly impairs both cognitive and physical performance. Long shifts, unpredictable schedules, and high-stress situations often lead to chronic fatigue, which reduces an officer’s working memory—the brain’s ability to hold and manipulate information in real time. This limits their capacity to assess complex situations under pressure, and it increases the latency of cognitive switching, the mental process required to shift focus between multiple stimuli or tasks. For an officer in the field, this could mean recognizing a potential threat but being delayed in shifting gears mentally to act on it, whether that involves deciding to engage, call for backup, or issue verbal commands. Fatigue-induced delays can stretch reaction times by precious seconds, which, in the context of police work, can lead to critical errors or missed opportunities to de-escalate situations. As critical situations are almost always unplanned in the reality of policing, a police officer may experience a high stress, high stimulus, situation towards the end of a long shift, this will directly impact the ability of that police officer to make the correct choice in actions, compounded with other significant variables discussed above, experience, training and overall speed of response.

Response: Physical Execution of Skill Under Stress

After the brain has processed visual input and interpreted the situation, the final step in reaction time is the physical response. This phase is dependent on a variety of factors, including motor coordination, muscle strength, and fine motor skills. In law enforcement, the ability to perform hard skills—drawing a firearm, applying restraints, or engaging in defensive tactics—demands not only physical fitness but also the ability to execute under high-pressure circumstances. Which often means that those police officers who are readily capable of meeting, and overcoming, such circumstances are those who have taken time to train appropriately in order to develop the mental pathways of skillset development. In contrast, as we saw with the female USSS agent who could not reholster her firearm, there are plenty who do not work on skillset development and reap the consequences of their inaction during high stress situations.

Motor responses are controlled by the cerebellum, which integrates sensory input with motor commands to ensure coordinated movements. However, in high-stress situations, the body’s sympathetic nervous system takes over, initiating the fight-or-flight response. This response floods the body with adrenaline, increasing heart rate, diverting blood flow to large muscle groups, and reducing fine motor control.

Why Repetition Is the Path to Mastery and the “Rise to the Occasion” Myth – is an article I wrote that details the science of this exact process, and why without repetitions of correct skillset actions, no one – especially not police officers – will be able to overcome the lack of skillset development.

This shift away from fine motor skills is particularly detrimental for tasks requiring precision, such as aiming a firearm, manipulating small objects like handcuffs, making correct statements while pressing a radio mic button, or deploying a taser. Studies have shown that during high-stress encounters, officers’ ability to perform tasks requiring dexterity decreases significantly. This can lead to slower or less accurate responses, further compounding the overall reaction time. This is not exclusive to police officers, however, this is the nature of the human condition.

The startle response—a reflexive reaction to an unexpected stimulus—can also impede performance. While the startle response is designed to protect the individual, it can cause involuntary muscle movements that interfere with intentional actions. For example, an officer may involuntarily flinch or tense up in response to a sudden noise, delaying their ability to draw a weapon or make a defensive maneuver. Police officers specifically, but anyone caught in a high stress situation is subject to the same real world issues – you do not (usually) get to choose the time, date, location and cirucmstances of a critical incident.

(right click - open image in new tab to zoom in - the above mapped chart of this article and see how to process this information)

Combined Impact of Low Light, Fatigue, and Distraction

Low light, fatigue, and distraction interact synergistically to severely disrupt an officer’s cognitive and motor performance by overwhelming the brain’s ability to process and respond to stimuli efficiently. In low-light conditions, the slowed recovery of retinal photoreceptors, particularly rods, delays visual input processing, impairing visual acuity and extending the time required to recognize threats. Fatigue further exacerbates this delay by reducing the brain’s working memory capacity and impeding cognitive switching—the ability to transition between tasks or stimuli—leaving officers unable to quickly interpret complex, low-contrast visual information. Additionally, fatigue diminishes motor coordination by disrupting the integration of sensory input with motor output in the cerebellum, resulting in slower and less precise physical responses. Distraction compounds these issues by overloading the brain’s attentional resources, triggering cognitive bottlenecks that hinder pattern recognition and induce inattentional blindness, where critical stimuli are missed. These combined factors—delayed visual input, impaired cognitive flexibility, and fragmented attention—work in tandem to elongate reaction times, causing split-second delays to stretch into dangerous seconds, heightening the risk of operational errors in high-pressure scenarios.

You don’t get to choose when a critical incident occurs, all you can do is have the skillsets needed to win developed beforehand.

How do I overcome these issues?

To overcome the compounded challenges of low light, fatigue, and distraction in high-stakes situations, police officers and responsible armed citizens must adopt a multifaceted approach that integrates both physiological conditioning and cognitive training. First, structured visual training should be implemented, focusing on improving visual performance in low-light environments. This includes through force on force, and dryfire practicing threat identification under varying lighting conditions, optimizing contrast sensitivity, and mitigating the impact of white light glare. Incorporating scenarios where photopic and scotopic vision is stressed can enhance an individual’s ability to transition smoothly between different lighting environments, reducing the delay caused by slowed photoreceptor recovery. Officers and armed citizens should also be trained to filter out irrelevant visual noise through attentional control techniques, thereby minimizing the effects of attentional blink during critical decision-making.

Fatigue management is equally essential and can be addressed through regulated sleep hygiene practices and shift scheduling to ensure police officers are not chronically operating under sleep deprivation. Physical conditioning, including cardiovascular and strength training, improves the body’s ability to resist fatigue, preserving both cognitive flexibility and motor coordination under prolonged stress. Additionally, officers should engage in skillset development under fatigue conditions to simulate real-world environments where decision-making and physical execution will be impaired. By training the cerebellum and motor cortex through the repetition of hard skills, like firearm handling or defensive maneuvers, under conditions of stress and exhaustion, officers can develop automaticity in their responses—thereby countering the degrading effects of fatigue and stress on fine motor control.

Finally, cognitive resilience to distraction must be built through scenario-based, professionally guided, force on force training that incorporates multiple sensory inputs, teaching officers and armed citizens to maintain focus and situational awareness in chaotic environments. This involves honing cognitive switching capabilities and pattern recognition under duress, so they can quickly and accurately interpret stimuli, regardless of distractions. By practicing decision-making under stress, Hick’s Law delays can be mitigated, allowing individuals to streamline cognitive processing despite a high number of possible responses. Taken together, these protocols establish a strong foundation for improved reaction time by enhancing visual acuity, reducing the effects of fatigue, and bolstering cognitive efficiency in the face of distraction. Through deliberate, evidence-based training, police officers and armed citizens can overcome the limitations of human physiology and improve their capacity to perform in critical situations.

If you want to follow some people online that are at the forefront of developing methodologies for overcoming these issues through real world, evidence based training programs, check out @centrifuge_blake, @centrifugetraining, and @the_adventures_of_will.i.am.

Leave a comment